For My Brother

In This Article

-

Between the ages of six and ten, I was convinced that my parents planned to leave me in the middle of the night, driven mad by my autistic brother, Matthew.

-

My family has been kicked out of restaurants, parks, and public pools; the stigma of autism following us like a dark cloud. To call our life chaos for those 12 years would be an understatement.

-

I will forever be a part of the autism community, but this membership has not been cheap.

Between the ages of six and ten, I stayed up every night waiting for the sound of my parents closing their bedroom door. Then I stayed up for an extra 20-30 minutes to make sure it didn’t reopen. I was convinced that they planned to leave me in the middle of the night, driven mad by my autistic brother, Matthew.

My parents did not abandon me, and Matthew remained with us for two more years before moving into a group home. A typical day during those 12 years started off with a 4-am wake up call, followed by one parent escorting my brother and me to the car for our morning drive. Matthew begged for food he would eventually just toss in the garbage, screaming “McDonald’s” or “Jack-in-the-Box” as we made our way down the still-dark streets of suburbia. Breakfast Jacks and hash browns made up about 50% of my diet during those years, while Matt was partial to chicken nuggets drenched in Italian dressing.

After he was fed, dressed, and cleaned up, my mom and I would harness him onto the school bus and send him on his way. About every other day my mom received a phone call while he was at school, explaining how he had soiled his clothes, self-injured, or bitten a staff member (they learned not to call unless he broke the skin). After school I was shuttled off to sports practice via a carpool for which my parents never drove. I fell in love with school and sports not necessarily for the academics or the athletics, but for the hours of relative silence and calm they were able to provide. I showed up early to appointments and stayed late, anything to spend time out of the house. When I arrived home after practice, my whole family sat down for dinner at the table together, a ritual my parents gathered us for, every day, without fail. Whether it lasted five seconds or 20 minutes didn’t matter; it was the only sense of normalcy we were able to achieve.

Homework was completed between guarding the food in the cupboards and rewinding Matt’s VCR tapes. Sometimes I was instructed to chase him around our tiny yard, my parents praying that physical activity would keep him silent for the night. At bedtime, his medications either drugged him into slumber or he was awake for the night, soiling his bed sheets or leaping from his window into the front yard. Before we had a lock on his room, he would creep down the hall, waiting for my father to shout “Back to bed!” and he would scurry back into his room as if it were a game.

Those 12 years of my life were characterized by Matt’s creaky outdoor swing set, thrice daily handfuls of pills, a constant parade of respite workers, padlocks on our fridge, trapeze bars hanging from the living room ceiling, and “Aladdin” playing on the VCR for ten hours a day. My family has been kicked out of restaurants, parks, and public pools; the stigma of autism following us like a dark cloud. To call our life chaos for those 12 years would be an understatement. The usual benefits of a sibling (shared chores, free advice, companionship) were lost. I was a pseudo-only child, shipped from one activity to the next while my parents were suspended in a sense of panic, wondering what injuries he would inflict on himself or whether he would be kicked out of another school. I love my brother so much, and one of the things that reminds me to be grateful is that all of the superficial things I missed out on due to his disability pale in comparison to the normal life he lost, and to the partial loss of a son my parents have already experienced.

I remember very clearly the last day Matthew lived with us, though I was unaware of its significance at the time. The soccer carpool had just dropped me off at home. Already physically drained, I was standing in the garage going through my usual mental preparation to enter the hellfire that would surely greet me inside. I was met instead with silence, my ears ringing from the anticipated noise. I found my dad in the kitchen; for the first time I realized how much older he looked than 40. “Where’s Matt?” I asked. Always the first question asked by anyone who walked into the house. “He’s staying away for a while. To work on his medications.” A while turned into five months at the adolescent psych hospital, where large men guarded every door and Matt sat next to anorexic girls at meal times (and stole their food). Five long months. Relief at home soon turned to confusion. My parents and I didn’t know what to do with ourselves. Even the dog had lost his daily job of chasing Matt onto the school bus. They kept me in the dark about his transition into a group home, sending me off to school and sports practices as if nothing had changed. I continued bringing home straight A report cards to tack onto the fridge, to remind them that they could still be hopeful about one of their children. Matthew has been in a group home since he left the psych hospital. He has not spent a night in his own home in ten years.

My parents have given me everything I need to succeed on my own, but even they will admit they have not been able to give me the attention they otherwise would have had my brother turned out “normal.” I resented this when I was younger, telling myself Matthew was faking his autism to get more attention. As I grew, I used this lack of attention to fuel early maturity and independence. I pushed my parents to let me travel, to send me to a brand new state for college, to not worry about me when they already had ten lifetimes of worry under their belts.

When I first settled in these new places such as college and medical school, I often struggled with how to explain my brother’s situation to new people. I hated getting pity from them, but I did not want to brush over Matthew like he hasn’t had a huge impact on my life. For a while when asked about my siblings, I would mention that I had a brother and leave it at that. No, he does not go to college, yes, he lives in California, yes, we get along.

Now I tell them everything, because there is nothing shameful or uncomfortable about him. I have an autistic brother. He lives in a group home with three other young men and an incredible staff. He likes “green chips” with Italian dressing. My parents visit him every week and they are in a constant battle to find the perfect balance of medications for him. I came to medical school to meet neurologists specializing in the care of autistic teens and adults. Yes, we get along.

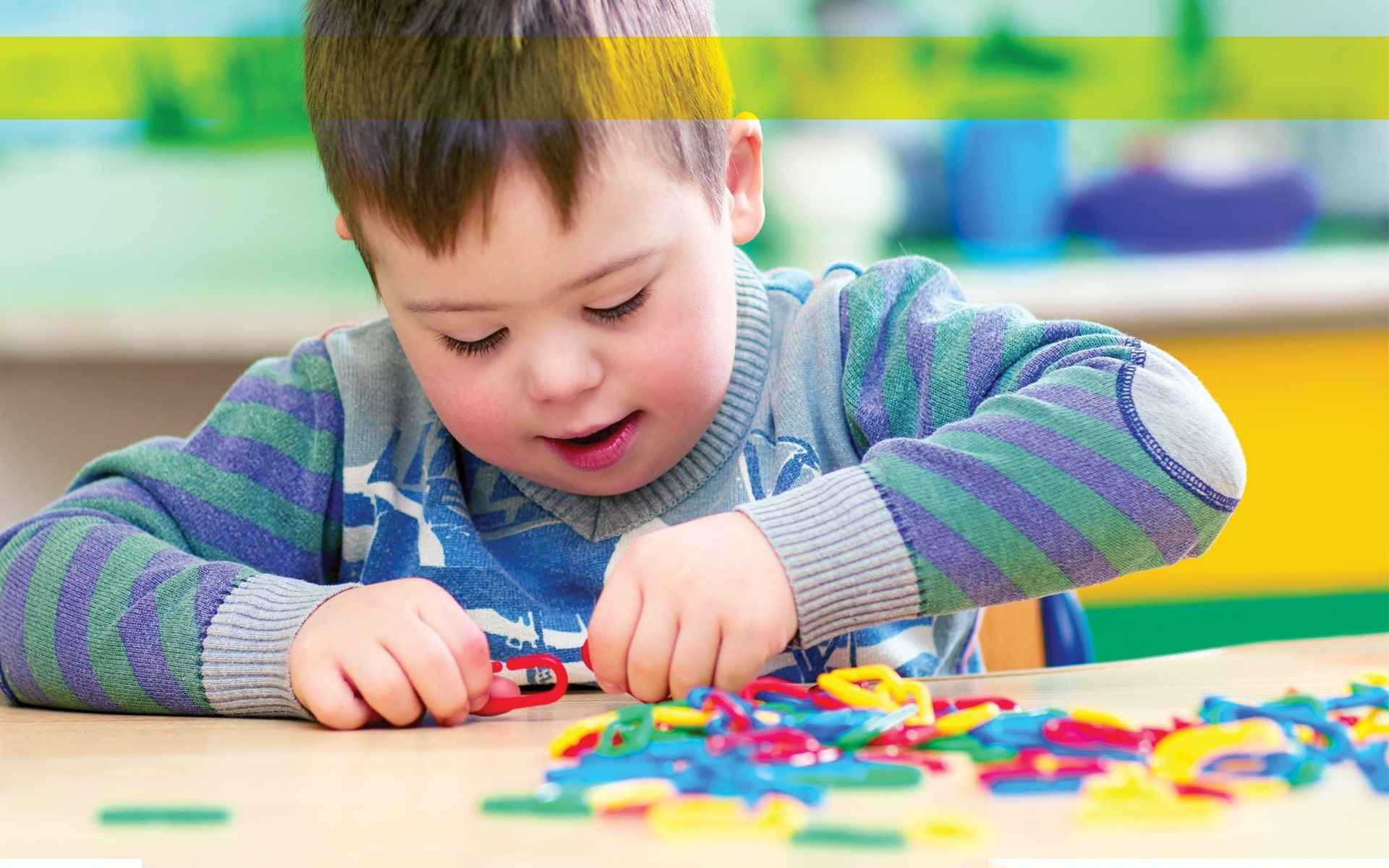

For four years I volunteered with a day program that serves autistic children and adolescents. It was the same program at which, five years earlier, my brother had been one of the first members. Pictures of him as a teen are still in frames around the house, and he is famous among the original staff members. “Oh, Matthew,” they would tell me, “He was wild. I loved that kid.” I loved the work and miss it dearly, but there was something incredibly frustrating about working with high-functioning kids on the complete opposite end of the autism spectrum from Matthew. These kids could talk, could engage, could make jokes with me. They had behaviors but they were manageable. I wondered how it was possible for them to wear the same diagnostic label as Matthew. Matthew, the boy who thinks he is still 14-years old, who cannot sit still for more than five minutes, who defecates in closets and smashes televisions against the walls. Matthew, who kicks dogs and bites humans. Matthew, who occasionally forgets who I am.

People say there is nothing worse for a parent than burying their own child. I think my parents are more afraid of Matthew outliving them. They sat me down when I graduated from high school to explain the significance of having a brother like Matthew. Someday my responsibilities for him may increase exponentially, and I need to be prepared for that. He will never not be my responsibility. Sometimes I feel like I am the insurance policy on my brother’s wellbeing, the one person my parents can fully and completely trust, the daughter they have vetted to be obedient and to work hard and to do it all for her brother. Someday I could be the only family Matt has left who knows him well enough to take care of him, to prevent others from taking advantage of him, and to give him the most fulfilling life possible as an adult with severe autism.

I will forever be a part of the autism community, but this membership has not been cheap. I’ve been challenged in ways that have forever changed me and how I perceive the world. I found strength in my family and in my education, both as a learner and a teacher. I can only hope that by sharing my Matthew story I will be able to connect, deeply, with others who may be feeling the same confusion, frustration, and joy that I have felt for the past 24 years.